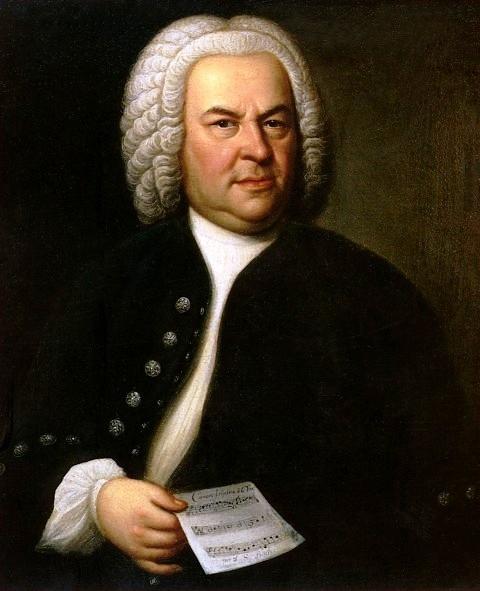

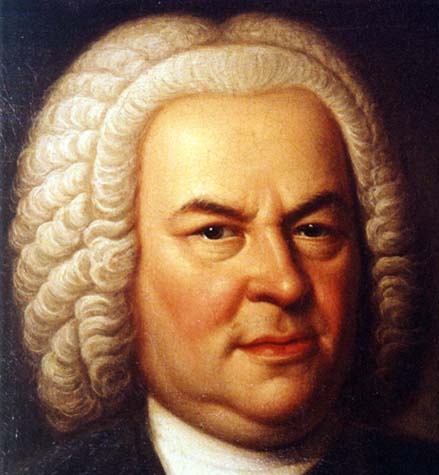

The 1748 Haussmann Portrait

Contrary to the 1746 Haussmann, there is nary a problem with the condition of the painted surface of the 1748 version [mr. Towe wrote in 2001 - A detail he doesn't discuss: The music sheet of the canon has been 'retouched' to add the necessary details (symbols) for performing this triplex canon à 6, mentioned in Gardiner 2013. Here the 1746 Haussmann is superior to the 1748, DW]. This portrait is now in the collection of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey, The painting is in a superb state of preservation, and it provides a wealth of detail that has, in effect, been cleaned off of the 1746 canvas or been obscured by repainting.

I can speak only of my own reactions. The 1748 Haussmann portrait is a powerful painting, one with a freshness, a vibrancy, and an immediacy that I do not feel while looking at the 1746 Haussmann portrait.

1746 1748

There is no denying that the picture's remarkable state of preservation is an important factor in the impact that it has on the viewer. In my own case, I can honestly say that that impact is undimmed after 34 years of "friendship." And, precisely because it is so well preserved, it is, as far as I am concerned, the principal and primary image to use for comparative purposes. While C. P. E. Bach had long been known to have owned an original Haussmann portrait of his father, its whereabouts remained unknown for over 150 years. That the painting had even survived was not known until 1950, when Hans Raupach announced its existence in his little monograph Das wahre Bildnis Johann Sebastian Bachs. The black and white photograph on the left is the frontispiece of Raupach's book, the color photograph is one that I took of the painting on November 8, 2000.

The 1748 Haussmann is not exempt from controversy, however, nor has it been immune to attack. Besseler, for example, dismisses it completely, preferring to rely instead on the 1791 ]. N. David copy of the 1746 Haussmann Portrait, a curious position, to say the least.

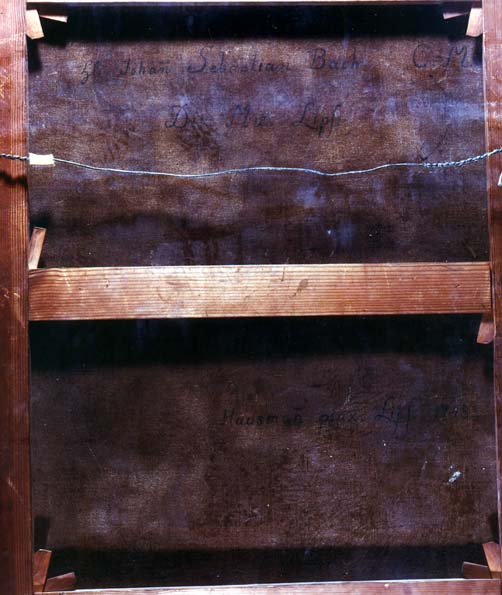

Part of the problem comes from what is evidently the only significant restoration to which the 1748 Haussmann portrait has been subjected. The canvass has been relined, and when it was relined, probably early in the 20th century, the inscription on the back of the original canvass was "transferred" (i.e., copied) on to the back of the relined painting.

Photograph by Greg Kitchen, © Teri Noel Towe, 2001

The problems with the transferred inscription, apparently, are two-fold.

-

First of all, the text of the inscription "deviates from Haussmann's usual type of signature." (Neumann, BDL, p. 402)

-

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the accuracy of the transcription of the date -- 1748, rather than 1746 -- has been a source of controversy.

There are several reasons for this. First, the "8" could be a misread "6". If that were to prove to be the case, a disconcerting anomaly would be explained away. The apparent two year discrepancy has gnawed at scholars, who consistently seem to assume that the replica had to have been a part of a "two for one" package deal that Bach negotiated with Haussmann. Such a "discount package" concept is appealing, but it is based on the assumption that the inscription originated with Haussmann, an assumption that I now reject as both unwarranted and incorrect.

I now firmly believe not only that the inscription did not originate with Haussmann, but also that it was added after the deaths of both Johann Sebastian and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. But a detailed discussion of why I have come to that conclusion will have to wait for another day, in part because I haven't done all of my homework on this question yet and in part because it is clearly way beyond the scope of this presentation. The provenance of the 1748 Haussmann is not certain, by any means, but the description that Burney provides in his 1772 account of his visit with C. P. E. Bach in Hamburg makes it clear that C. P. E. had the painting in his possession by that time. The next gap comes after his death. That the painting remained in the possession of his widow and spinster daughter is proven by its inclusion in the official estate inventory of 1790. Who bought it when it was eventually sold in 1796 or 1797, is not known, but, according to the Jenke family, from whom Bill Scheide obtained the painting in the early 1950s, the painting had been acquired "from a Berlin antique dealer sometime after 1800" (Neumann, BDL, p. 402). Certain tantalizing clues on the back of the frame and on the stretcher suggest, however, that the painting changed hands more than once between its sale by the heirs of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and its acquisition by the Jenke family, whenever that took place during the 19th century. When Bill graciously allowed me to make my own photographs of the painting for the first time last November, he also graciously permitted the examination of the painted surface with a so-called "black light". This ultra-violet light causes buildups of varnish to turn an eerie olive green and recent overpainting to turn dark and opaque. Our examination of the painted surface of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait revealed that, apart from one tiny repair to the background, a repair that is documented, the paint is pristine and as "original" as it was the day it left Haussmann's studio. It may never be "proven" that the 1748 Haussmann Portrait is a portrait from life, as I believe it to be, and not a replica of the 1746 Haussmann Portrait, but those who have been in the presence of the original will need no convincing.

No description of this icon of musical portraiture could possibly be more accurate or more eloquently expressed than Christoph Wolff's explanation of the raison d'etre for the Haussmann portraits in his new monograph, Johann Sebastian Bach, The Learned Musician; with one significant exception that will become obvious in a few minutes, it cannot be bettered, and I hope that Christoph, who is a valued colleague and friend, will forgive me for quoting it in extenso:

"When portrait painter Elias Gottlob Haußmann depicted the Leipzig town council in 1746, he painted the councillors in their official likenesses -- in serious pose, formal attire, periwig, and sometimes with specific attributes identifying their function....The same pattern applies to Haußmann's portrait of Bach..., in which the subject's right hand holds a page of music, but not just any old music. The cantor shows us a sheet inscribed with three short lines of musical notation and the inscription, Canon triplex à 6 Voc[ibus]per J.S. Bach (triple canon for six voices, by J.S. Bach), an encoded text whose complex musical contents would remain obscure to the general viewer and challenge even the well versed musician. A similar portrait by Haußmann of Johann Gottfried Reiche (1727), senior member of the town music company, shows Reiche holding his trumpet and a sheet of music bearing an extremely difficult passage -- one that probably only he could play.

Bach displays what he considers his trademark, the short but highly sophisticated canon, BWV 1076, an emblem of his erudite contrapuntal art. By not having a keyboard instrument included in the picture, he chose to disclaim his fame as a virtuoso performer. And by not clasping a paper roll, the conductor's attribute (As Johann Hermann Schein, an earlier Thomascantor, does in his portrait), Bach elected to play down his office as cantor and music director. The austere expression worn by the composer in this [so far]only authentic portrait corresponds well to the musical statement.

In the portrait, Bach the man takes a back seat to his work, and this is how we have always understood him, and how we ordinarily see him: compared with his imposing oeuvre, the human being seems of secondary importance." (Wolff, JSBTLM, 2000, pp. 391 - 392, footnotes omitted)

The distinction between the "public" Bach and the

"private" Bach, the distinction between Bach as a professional musician and Bach

as a musical intellectual, is of crucial importance, not only to the

understanding of the Bach iconography as a whole but also to the raison d'etre

for the lost Kittel portrait, and therefore to the Weydenhammer Portrait

Fragment, in particular. And the effects of this distinction should not be

discounted or overlooked. Christoph Wolff's compelling observation that,

"compared with [Bach's]imposing oeuvre, the human being seems of secondary

importance" has implications that go far beyond the distinction

between the public Bach and the private Bach. That so few of us are as

concerned with Bach as a human being in general, and with

what he looked like in particular, as we are with his "imposing oeuvre",

the Himalayas of Western music, also means that most do

not really care what he looked like and therefore have not troubled to

study his face and his physiognomy to the degree that they

otherwise might. Most think that they know what he looked like, but, as

we shall see in our examination of his physiognomical

characteristics, all of us, in fact, know his face much less intimately

than we think.

There can be no doubt in anyone's mind that the

persona we see in the Haussmann portraits is the persona that Bach

sought to

immortalize visually in the only portrait image that, so far, he is

known to have commissioned, and even then perhaps with some

reluctance and trepidation. The Haussmann image is Sebastian Bach

as he wanted himself to be seen by posterity, and, when one

considers the multitude of images that have been derived from this basic

image over the course of the past 250 years, it is clear that

in that goal he succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. It is

everywhere, and its omnipresence subliminally tints our attitudes

towards "competing" personae with a power that borders on the

draconian. The Haussmann Bach is on coffee mugs. It is on

sweatshirts. It is on bar towels and tote bags. It is on the sides of

buildings. There are psychedelic versions and surreal ones. It is

on chiming clocks and foulards. It has even been the model for a

porcelain coffee pot.

The Haussmann portrait of Bach is the equivalent of the Athenaeum Portrait of George Washington.

Teri Noel Towe, 2001

go home or...

|

Erfurt Bach |

Haussmann 1746 overpaint removed |

Haussmann 1748 copy or original? |

Volbach

the old Bach? |

|

|

|

|

Dick Wursten (dick@wursten.be)