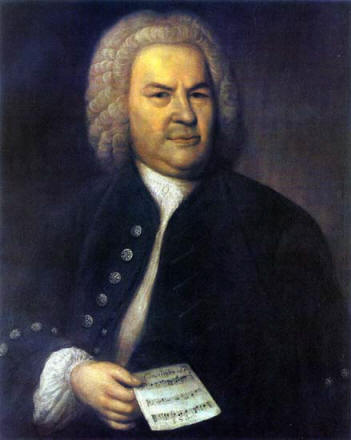

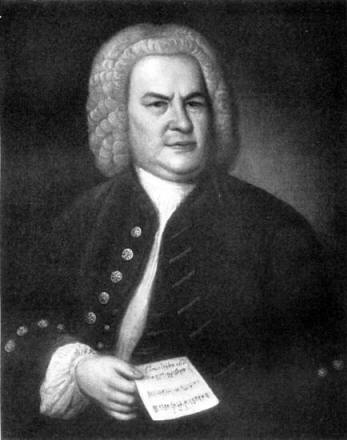

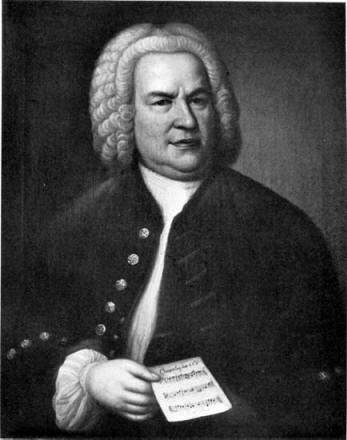

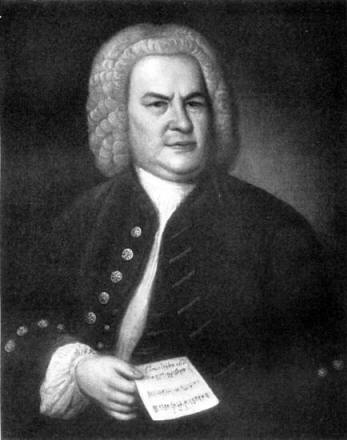

The 1746 Haussmann Portrait

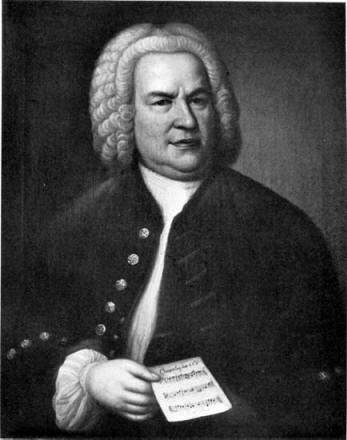

The 1746 Elias Gottlob Haussmann portrait, now in the Altes Rathaus in Leipzig, that has been described by more than one commentator as the "Ursprung" of Bach iconography. It is so called simply because it is both the earlier and the much longer known exemplar of the two authentic portraits from life that Haussmann is so far known to have painted of Johann Sebastian Bach. Sadly, the 1746 Haussmann has had less than an easy time of it over the course of two and a half centuries. Here is how most of us think of it, in the form that it took after the 1913 Restoration, undertaken by Walter Kühn and supervised by Albrecht Kurzwelly: photograph, from the late Werner Felix's 1985 monograph on Bach (to the right a more recent reproduction, -- and a link for those interested in the canon à 6, dw ):

For the present, I shall bypass the discussion of the

problems with the provenance of the 1746 Haussmann, the whereabouts of

which between 1746 and 1801/1802 cannot be documented with any certainty

whatsoever, and focus on the problems associated

with its condition. The 1746 Haussmann portrait is to the Bach

iconography what "The Last Supper" is to the da Vinci

iconography: the unfortunate victim of generations of good intentions.

Relatively early on, I surmise during the years immediately

after August Eberhard Müller gave it to the Thomasschule

at the time of his departure to take up his duties as Court

Capellmeister in

Weimar, the painting hung in some sort of a heavily trafficked and

regularly used public venue and became coated with grime, soot,

and God knows what else. Hilgenfeldt remarked on its poor estate in 1850

(and he was not the first): "A pity that time has begun to

have its effect on the painting," he wrote. "It is much darker and the

outlines are becoming blurred." (Neumann, BDL, page 401) Prof. Neumann recounts the subsequent history tersely:

"In 1852, it was 'freshened up' and in about 1879 the Dresden landscape painter Friedrich Preller the younger (1838-1901) restored it drastically and overpainted it heavily. When Bach's bones were identified in 1894/95 the Berlin restorer Schönfelder cleaned and renovated it once more and contemporary reports said that the effect was 'distinctly more expressive and detailed' (His II) than after the recent overpainting." (Neumann BDL, pp. 401-402)

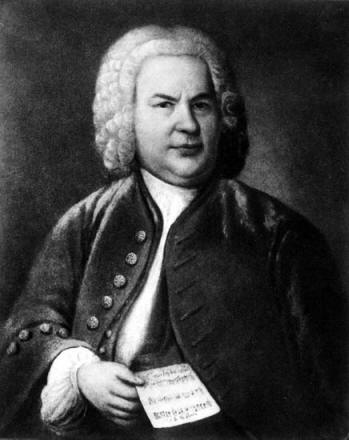

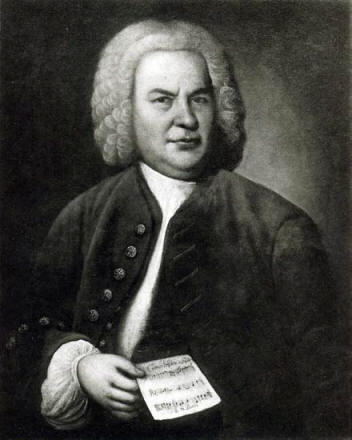

On the left is a photogravure that, I believe, shows what the painting looked like after Preller had worked on it. The photogravure on the right (one of the plates in the Exhumation Report of 1895) shows the canvas as it looked immediately after the Schönfelder restoration.

Prof. Neumann continues:

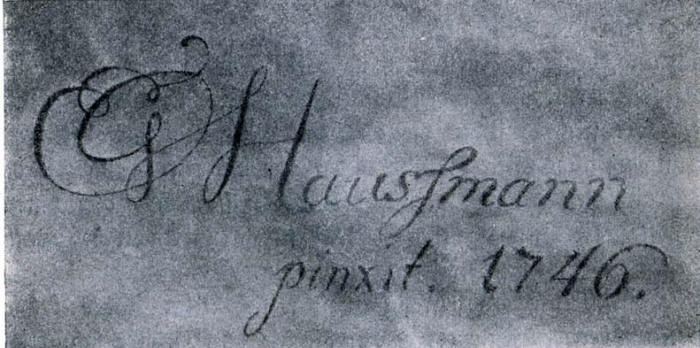

"In 1913 it was presented on permanent loan to the Stadtsgeschichtliches Museum of Leipzig whose then director, Albrecht Kurzwelly, had it 'thoroughly put in order with modern methods of restoration... by the Leipzig painter Walter Kühn (1855-1929), who had a long-standing reputation as a picture restorer' [citationJ, in the course of which the original signature was uncovered, ..." (Neumann BDL, p. 402)

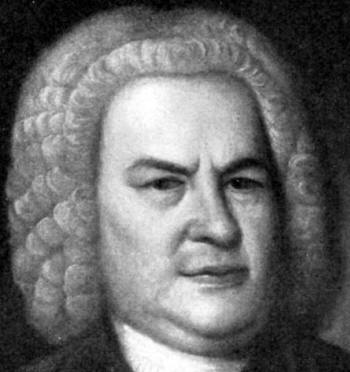

A lot more than the signature was uncovered. Kurzwelly and Kühn cleaned off all of the overpaint that the previous restorers had added in the course of their respective efforts. In other words, Kurzwelly and Kühn removed all of the paint that they did not believe to be Haussmann's. Here is the result, juxtaposed with a contemporaneous photograph of the painting as it looked after Kühn had finished his careful and conservative "in painting":

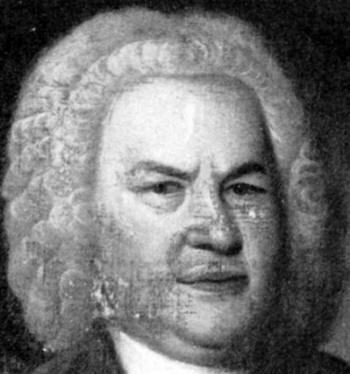

And here is the same "before and after", but this time

a close-up of the head.

The damage to the surface of the painting is heartrending to contemplate. The loss of paint on the face has been great, but, gruesome as the comparison is, it is one that must be made, simply as a reminder that the image that we all carry in our psyches of the 1746 Haussmann portrait is not necessarily -- in fact, almost certainly isn't -- the image that left Haussmann's studio in 1746. Amongst other things, the restored 1746 Haussmann portrait cannot be relied on to supply a reliable standard for the shape of the bridge of the nose, the upper lip, much of the lower left lip, much of the right cheek and jowl, much of the upper left cheek, and a significant portion of the right eyelid. The white spots, by the way, indicate the places where the original paint and priming coat, or bolus, had disappeared right down to the surface of the canvass, necessitating the careful application of gesso to the surface of the canvass to bring those areas back up to the level of the bolus surface so that the restorative "in painting" would be even with the remains of the original painted surface. The dark grey areas, such as those across the bridge of the nose and the upper left cheek are the places where Haussmann's original painted surface has been abraded, down to the bolus.

In trying to make the correct decisions when "in painting" the damaged areas to make the painting at least presentable to an eager viewing public, Walter Kühn appears to have relied to a great extent on a direct copy of the painting that had been made a few years before it was "restored" for the first time. It is believed that that painting is the copy painted by one Friedrich of Braunschweig in 1848, the one that is described by Hilgenfeldt as "said to have been excellently realized in every respect". (Neumann BDL, p. 403)

The illustration comes from the Bach Jahrbuch, 1914,

in which the painting's existence was disclosed by Prof. Kurzwelly. On

both

"stylistic and technical evidence (matt paint, "biedermeier" gold frame,

type of canvas and wedge framing)", Kurzwelly suggested

that it was "possibly connected with the copy of the [1746 Haussmann]attested by Hilgenfeldt in 1850." (Neumann, BDL, p. 403) It

cannot be said for certain the copy by Friedrich to which Hilgenfeldt

alludes, however, because the canvas is not signed or dated. When the copy is placed beside the original, as

restored by Kühn , the degree to which it influenced Kühn is easy to

discern, and

there can be no doubt that, despite some obvious differences, what

appears to be fundamentally a meticulous copy of the 1746

Haussmann original has evidentiary value, as a secondary source of

significance.

copy of the original (?) 1848

restored Haussmann 1746

The 1746 Haussmann portrait has been restored again recently, and in its present state it may now arguably be truer to the

Haussmann original than Walter Kühn's restoration was, but, as a primary source of information about Bach's physiognomy, its

value is severely limited. The 1746 Haussmann portrait is useful as a "back up" and as a corrective, nothing more.

Teri Noel Towe, 2001

go home or...

|

Erfurt Bach |

Haussmann 1746 overpaint removed |

Haussmann 1748 copy or original? |

Volbach

the old Bach? |

|

|

|

|

Dick Wursten (dick@wursten.be)