The Inscrutable Volbach Portrait

Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit

The Authenticity of the Volbach Portrait

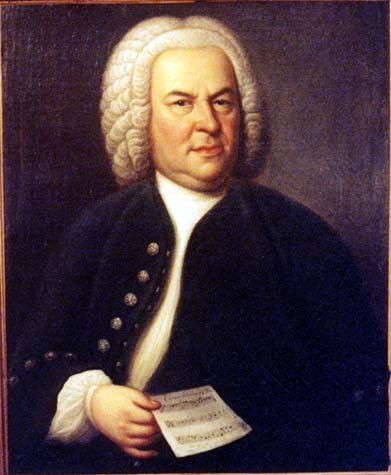

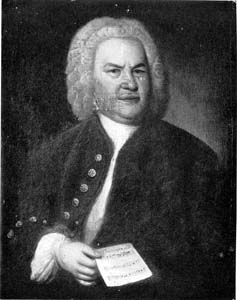

Altersbild eines unbekannten Meisters aus dem Besitz von Prof. Volbach, it says on an old postcard. Professor Volbach is Fritz Volbach (1861-1940), who acquired the painting in 1903.

Gerhard Herz's perceptive and meticulous 1957 review (Musical Quarterly, Vol. XLIII, pp. 116-122) of Heinrich Besseler's Fünf echte Bildnisse Johann Sebastian Bachs, (Bärenreiter, Kassel, 1956) tells us that the painting had come to the United States and that it was in Fort Worth, Texas, where Fritz Volbach's son, Walther, who had inherited it, taught Theater Arts at Texas Christian University. The widespread resistance to the possibility that the Volbach Portrait might be an authentic and accurate depiction, taken from life, of the face of Johann Sebastian Bach is based essentially on two grounds:

Few can bring themselves to believe that Bach could have aged so much after the Haussmann portraits were painted; and

-

There are not only no known contemporary references to the image but also no known solid reasons for its existence, for its having been painted during the last weeks of Bach's life.

Please, therefore, let me begin by discussing the question of Bach's appearance during the last months of his life, because, as I previously have observed, if the Volbach Portrait is to be acknowledged as a genuine, authentic, and accurate portrait from life of Johann Sebastian Bach, it has to have been painted during the last months, if not the last weeks, of his life.

As Christoph Wolff so cogently has demonstrated, Bach's health deteriorated quickly, and it is clear that, by the late spring of 1749, he was most unwell. That the collapse was precipitous, like a falling house of cards, is made clear by the fact that, while Bach had been able to put on a full scale performance of the Johannespassion, BWV 245, on Good Friday, April 4, 1749, by June 2, 1749, the Saxon prime minister, Graf von Brühl, was able to write to one of the Leipzig burgomasters and, in essence, demand that the director of his private musical establishment, Gottlob Harrer, be allowed at once to audition to succeed to the posts of Thomascantor and Director musices of the City "upon the eventual...decease of Mr. Bach." (Wolff, J.S.Bach. The Learned Musician (2000), p. 442) Bach rallied, however; on June 19, he took holy communion in the Thomaskirche, and, on August 25, at the annual Rahtswechsel service, he put on a performance of the elaborate and festive Cantata, Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir, BWV 29. For this performance, he himself wrote out a new continuo part for the "Sinfonia", a part that graphically shows how much his handwriting had deteriorated. (Wolff, 2000, p. 444-445) Bach's last known signature is on a letter dated December 11; by December 27, he was no longer able even to sign his name; on the last document that he is known to have dictated, "the signature was supplied by a scribal hand." (Wolff, 2000, p. 447). It was at the end of March, 1750, sometime between the 28th of the month and the 31st, that Bach was operated on for the first time by the esteemed English ophthalmic surgeon, Chevalier John Taylor, one of the pioneers of modern eye surgery.

"Taylor, a specialist in cataract operations, was well respected, and by no means a charlatan." The first operation was not successful, and between April 5 and April 8, 1750, Taylor operated on Bach's eyes again. The "operation..., as the Obituary [prepared by C. P. E. Bach and Agricola]states failed; matters were made worse by 'harmful medicaments and other things'..." (Wolff, 2000, p. 448) In his autobiography, published in 1761, Taylor himself acknowledged that the operations on Bach's eyes had been unsuccessful:

"...at Leipsick, where a celebrated master of music, who had already arrived to his 88th year, received his sight by my hands; it is with this very man the famous Handel was first educated, and with whom I once thought to have had the same success, having all the circumstances in his favor, motions of the pupil, light, etc., but upon drawing the curtain, we found the base defective, from a paralytic disorder." (Quoted by Wolff, 2000, p. 449)

For our particular purposes, what is the import of this sad tale? First, the deterioration in Bach's health, and the resulting toll that it must have taken on his physical appearance, did not begin until at least six months after the latest possible date for the painting of the 1748 Haussmann portrait. Second, no one seems ever to have stopped to assess carefully the significance and the implications of Chevalier Taylor's recollection of the event, more than a decade later. First of all, that he could have confused Bach's name with that of Handel's teacher, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow (or Zachau) is understandable; after all, Dr.Taylor was an Englishman writing many years after the fact, and the first syllable of Zachow's name rhymes with Bach. But what is even more significant is Taylor's specific statement that "the celebrated master of music" was in his 88th year. (Zachow, who was born in 1663, would have, in fact, been in his 88th year in 1750.) Had Bach's physical appearance been as it is in the 1748 Haussmann portrait, there is little likelihood that, even in retrospect, Taylor, a physician and surgeon, would have believed for a nano-second that his Leipzig patient had been 87 going on 88. If, however, the man upon whose eyes Taylor operated looked like the man in the Volbach Portrait, such an error could easily be made.

Now, a comparison, anatomical detail by anatomical detail of the face in the Volbach Portrait with the face in the 1748

Haussmann Portrait, focussing on the physiognomical characteristics that an

accurate and authentic depiction of the face of Johann Sebastian Bach must have.

As I did in demonstrating that the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment is an

authentic and accurate depiction of the face of Johann Sebastian Bach, I shall

begin at the top, and work downwards. Once again, I shall use the 1748 Haussmann

Portrait as the absolute standard, but, yet again, I shall also include the

equivalent details from the 1746 Haussmann Portrait as a reminder that that

painting, sadly, is not reliable for comparison purposes. The details from the

1748 Haussmann portrait are on top, or to the left, as the case may be, the

details from the Volbach Portrait are in the center, and the details from the

1746 Haussmann Portrait are on the bottom Finally, unless otherwise indicated,

left and right are from Bach's perspective.

But, before I focus on the face, please let me point out that the similarity of

the basic pose in these two "brustbilder" allows one to compare the slope of

Bach's shoulders. He slouched, so to speak, as some might expect of a keyboard

player, and the distance from his neck to the juncture of shoulder and upper arm

(I hope the doctors and scientists who are reading this will forgive the artless

inexactness of my descriptive language!) seems to be greater, and the angle of

the slope thus less acute, on his left side than it does on his right.

Significantly, this subtle anomaly, which is apparent in both the 1746 and the

1748 Haussmann Portraits, is also apparent in the Volbach Portrait. The sharper

angle of the junction of the right sleeve with the body of the coat in the

Volbach Portrait also reinforces my contention that the Bach of the Volbach

Portrait weighed significantly less than the Bach of the Haussmann Portraits.

And now the direct comparison of the faces.

First, the faces, without the distractions of perruques and costumes:

I do not have any trouble at all concluding that the face in the center is the face on the left and on the right, affected by serious, ravaging, and enduring illness.

And now the specific comparisons, detail by detail, beginning with the distinctive, furrowed brow. (I apologize for the relatively small size of the images, but, pending the arrival of the recently made 8x10 transparency of the painting, I am limited by the relative graininess of the available image. Larger scans will supplant these as soon as it is feasible.)

The asymmetry, the distinctive arch, and the upward creases are the same, but there has been significant hair loss. One can still make out the arches of the brow, but there is much less hair, a logical effect of stressful illness.

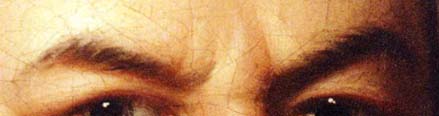

Now, the eyes:

Once again, the similarities are astonishing. Because of the graininess of the photograph of the Volbach Portrait it is difficult to clearly analyze the right-hand portion of the drooping eyelid over the right eye, but the distinctive fold that the drooping eyelid takes as it meets the bridge of the nose is not only in the same location but also more pronounced in the Volbach Portrait, which would make sense if it had been painted at least a year and a half after the 1748 Haussmann portrait. The drooping eyelid over the left eye lags behind that of the right, as it does in the 1748 Haussmann portrait. Also, the distinctive curve of the portion of the lower right lid nearest to the bridge of the nose appears to be the same.

Until I have seen and studied at least the new 8x10 transparency, if not the original of the Volbach Portrait itself again, however, I shall offer no firm comment on the color of the eyes, but I will make the observation that the color is blue-grey in the reproduction used for this initial comparison. Also, the bags beneath them appear to be the same.

I continue, however, to be struck by the peculiar rendering of the left eye; the watery, cloudy nature of the base of the pupil supports, I think, my personal belief that the Volbach Portrait was painted after the eye operations.

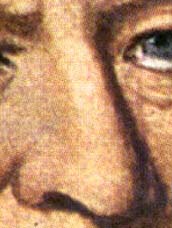

Next the nose:

Yet again, the similarities are

astonishing. Again, the graininess of the photo of the Volbach Portrait

is something of an impediment,

but the essential shape of the nose is identical, and the little ridge

on the lefthand side of the bridge of the nose about a third of the

way down can be made out. And, sadly, the nose of the 1746 Haussmann Portrait is

one of the areas in which the damage has made it unreliable for comparison

purposes.

And, now the mouth and jaw. As I have shown elsewhere, in an analysis of the

essential elements of Bach's facial physiognomy, an underbite, a protuberant lower jaw, and the absence of teeth are essential.

Once again, the essential elements appear

to be present. The lower jaw appears to protrude beyond the upper one,

and the upper lip

is sunken on the left hand side in the same spot that it appears to be in the

1748 Haussmann portrait. The shape of the right hand side of the lip is clearly

different, however, and the distinctive creases are longer. These differences in

detail are telling. First, it might be indicative of the loss of additional

teeth between 1748 and the spring of 1750. Secondly, Chevalier Taylor makes a

specific reference to a paralytic disorder. Is it possible that the beginnings

of the deterioration of Bach's health are attributable to a stroke and that he

suffered at least one, and perhaps tw0 more, before his death? It certainly

would comport neatly with the kind of essential physical problems that Christoph

Wolff suggests were the root cause of Bach's last illness. A mild stroke would

also neatly explain (1) why Graf von Brühl moved with all deliberate speed to

railroad the Leipzig Town Council into audtioning Bach's eventual successor,

Gottlob Harrer, (2) Bach's recovery in the summer of 1749 and (3) the initial

problems with his handwriting, particularly if the stroke was on the right hand

side, and I know of no evidence to suggest that Bach was left-handed. As

Christoph Wolff has demonstrated, Bach was not able even to sign his own name

after December 27, 1749, an indication of yet another stroke.

Of course, the effects of the strokes provides a cogent and logical explanation

of the "problem" of the dimple or cleft in the chin that Bach seems to have in

the Volbach Portrait. I have examined the issue in some detail in The Queens

College Lecture of March 21, 2001, The Face Of Bach - The Search for the

Portrait that Belonged to Kittel, so, for the purposes of this analysis, suffice

it to say, that the Bach of the 1746 and 1748 Haussmann portraits was corpulent,

to phrase it politely, and certainly a minimum of 25 to 30 pounds heavier than

the Bach of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment or the Bach of the Volbach

Portrait. The loss of weight that was an inevitable by-product of the rigors of

Bach's precipitous physical decline and the associated health problems,

including at least one, and possibly as many as three strokes, before the stroke

that ultimately caused his death on July 28, 1750, surely would have "uncovered"

the cleft that the the subcutaneous fat obscures in both the 1746 and 1748

Haussmann portraits.

As far as I am concerned, the Volbach Portrait passes the physiognomical

comparison test convincingly, but is there anything else about this

extraordinary image that might independently support the

conclusion that it is a portrait from life of Johann Sebastian

Bach painted in the last months of his life? As it happens, there is.

First, let's look at the the Volbach Portrait together with both the 1746 and

1748 Haussmann portraits again.

One cannot help but be struck by the fact

that, with one telling exception, the pose in the Volbach Portrait is

for all practical

purposes the same as that of the the 1746 and 1748 Haussmann portraits. That

significant exception, of course, is the Volbach Bach is not proffering a copy

of the Canon triplex à 6 vocibus to the viewer. Instead, almost symbolically if

one believes, as I do, that Bach was partially disabled, if not paralyzed, on

the right side during the last months of his life, his right arm is shrouded by

the cape that has been draped around his shoulders. How else could Sebastian

Bach send a message to the knowledgeable spectator that this portrait does, in

fact, depict the same man as the 1746 and 1748 Haussmann portraits? Anyone who

has spent any time studying Johann Sebastian Bach is well aware of his obsession

with numbers, numerology, and numerological equivalents, and also knows that the

Bach number is 14. (B=2 + A=1 + C=3 + H=8 = BACH=14) I cannot believe that in 35

years I never had bothered to count the buttons, but until the morning on which

I relented and, ready or not, wrote this essay, I never had.

There are seven buttons on the coat, and 14 on the waistcoat. That one set of

buttons is the Bach number, and the other is half that number cannot be

coincidental, and it suggests compellingly that, in fact, whether he could see

it or not, Bach did have "input" into the form and substance of the portrait.

The presence of the 14 buttons on the waistcoat reflects the reality, first

noticed by the great Bach scholar Friedrich Smend a half a century ago, that the

total number of buttons on the jacket and vest of the 1746 Haussmann Portrait is

14. (Why there are a total of 17 buttons either wholly or partially visible on

the garments of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait is an anomaly that has yet to be

explained.) And, the total number of button holes visible on the garments of the

Berlin Portrait is also 14.

And now, what about the issue of why? Why and for whom was the Volbach Portrait painted?

The answers to that question remain to be

ascertained, but, in light of the fact that it appears that we are, in

fact, dealing with a

genuine portrait from life of Johann Sebastian Bach, painted in the last

weeks of his life, research into issues that only a few days

ago seemed of little significance now becomes both important and

imperative.

- First, for whom was it painted, and why? I

believe that I have figured that out.. Mr. Towe then promises a

publication of his hypsothesis (after testing), but...He resumes: One thing is now certain. Like it or

not, those of us who are fascinated by the Bach iconography now must

come to grips with

the inscrutable Volbach Portrait. So far, the arguments in favor of its

being both genuine and an accurate depiction of the face of

Johann Sebastian Bach far outweigh the arguments against.

No longer can the Bach scholarly community turn its back on the Volbach Portrait, a shattering image, an image that shows Johann Sebastian Bach as he prepared to cross from this world to the next.

Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein.

Lieber Herr Gott, wecke uns auf...

Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit.

Teri Noel Towe

August 28, 2000

Revised April 11, 2001

edited and re-published 2014 Dick Wursten

go home or...

|

Erfurt Bach |

Haussmann 1746 overpaint removed |

Haussmann 1748 copy or original? |

Volbach

the old Bach? |

|

|

|

|